Online literature, dramas, games riding on fictional adventures of martial artists in ancient China prove popular in SE Asia

When Singaporean Tong Weiqiang watched Hong Kong wuxia, or martial arts, dramas more than 10 years ago, he was impressed by the plots and the costumes depicting such combat and chivalry.

He even pioneered a local hanfu movement to promote this traditional attire for Han Chinese and founded the Singapore Han Cultural Society in 2012 to attract more enthusiasts.

Tong said he first became interested in traditional culture at a tender age through The Four Books (The Great Learning, The Doctrine of the Mean, Confucian Analects, and The Works of Mencius) and classic novels such as Dream of the Red Chamber and Journey to the West.

Later, he read wuxia novels by writers including Jin Yong, Gu Long and Liang Yusheng, and has remained a fan of the genre.

“Many people in our cultural society also began to learn about hanfu from these costume dramas,” he said.

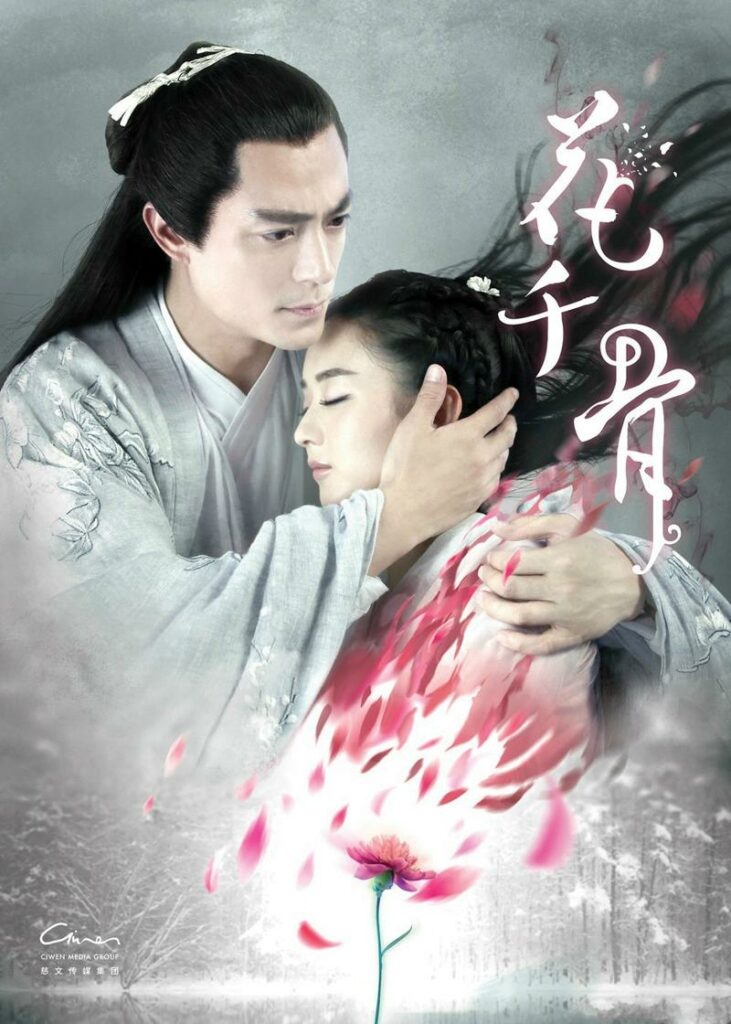

In recent years, with the increased popularity of Chinese cultural works such as dramas and online literature, wuxia-related content has started to regain its popularity with overseas audiences, including those in Southeast Asia.

Nguyen Truc Thuyen, a head of the Chinese division at the University of Foreign Language Studies at the University of Da Nang in Vietnam, said that unlike traditional wuxia, the modern form of the genre popular in Southeast Asia is a broader concept that includes xianxia (immortal heroes) and xuanhuan (fantasy featuring adventures and wars).

“Nevertheless, wuxia, or content that contains some elements of wuxia, is still very popular,” Thuyen said.

Tong Ye, founder and CEO of funstory.ai, a publishing-related tech startup, said many xuanhuan novels combine the martial arts sector, better described as jianghu in ancient times, with the modern style.

Jianghu translates as rivers and lakes. Metaphorically, it refers to the kung fu world of martial artists, assassins, wanderers and other characters popularized by wuxia.

Established in 2017, funstory.ai is a platform that uses artificial intelligence for digital overseas publishing to help promote the international dissemination of Chinese literary works. It has helped more than 100 Chinese online literature companies, including iReader Technology Co, to bring nearly 10,000 novels to some 50 international platforms such as Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple Books and Google Books.

Tong Ye said half the novels on the funstory platform are xuanhuan and xianxia books, adding, “Whether in Southeast Asia or North America, a substantial number of fans are following this kind of content.”

He said the rapid development of online literature in the past decade has made it easier to attract readers through serialized fiction. Online novels that combine fantasy with romance or elements such as witches also cater to readers’ tastes.

The global expansion of China’s cultural products has advanced significantly in recent years. Last year, the nation’s foreign cultural trade saw robust growth of 38.7 percent year-on-year — exceeding $200 billion for the first time, according to the Ministry of Commerce.

With a huge fan base, online literature has become a forerunner for Chinese cultural and entertainment content reaching overseas audiences.

As of 2020, more than 10,000 online literary works had entered overseas markets, attracting over 100 million foreign readers, according to a report by the China Writers Association last year.

The copyrights of more than 4,000 physical Chinese online literary works have been exported to countries and regions worldwide, including Southeast Asian nations such as Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar.

Wuxiaworld, a web novel site founded by Chinese American Lai Jingping in 2014, attracts millions of page views per day from users in more than 100 countries. Most of the users come from North America, Southeast Asia and Europe.

A great deal of wuxia-related content is being introduced to Southeast Asia from China in the form of dramas and movies.

For example, the television series Word of Honor gained over 100 million views on YouTube last year, with Southeast Asia among the regions with the highest number of viewers for the production.

Due to the impact of Chinese wuxia, xianxia drama and online novels, Southeast Asian audiences have rushed to play related games.

In the 30 days to Sept 12, nearly 25 percent of the mobile games advertised in Southeast Asia were based on ancient Chinese culture or style, with many of them related to well-known wuxia works, according to mobile advertising intelligence and analysis platform AppGrowing.

Lily Lee, vice-president of YouCloud, which operates AppGrowing, said, “Due to geographical and cultural factors, Southeast Asian users tend to have a higher acceptance of wuxia or other themes with strong Chinese characteristics.”

In addition, in view of the number of Chinese in the region, Lee said many wuxia games entering the overseas market focus on Southeast Asia, especially Singapore and Malaysia.

More than 30 million Chinese live in Southeast Asia, accounting for about 6 percent of the region’s population.

Lee said the new wuxia game Dragon Oath 2 was launched first in Singapore and Malaysia when it was released earlier this year.

“Although wuxia is a unique Chinese culture, the core spirit of pursuing freedom and justice is universally recognized by people all over the world,” Lee said.

She added that martial arts moves can be shown in games by using special effects and technology to provide an attractive visual experience, which is also why international players are willing to try wuxia-related games.

In Thailand, many young people have become obsessed with wuxia through games, rather than novels or dramas, according to Yazhou Zhoukan, a Chinese-language news weekly in Hong Kong.

The publication noted in a report that games based on wuxia novels such as The Legend of the Condor Heroes, which are imported to Thailand with a Thai language version, have become popular. Young people have also created websites to discuss wuxia, while sites such as Pantip publishing wuxia novels in Thai.

Thuyen, from the University of Da Nang, said the popularity of wuxia-related Chinese dramas, novels and games also attract people in Southeast Asia to learn more about Chinese culture.

“Many of my students choose to learn Chinese after reading wuxia novels. They not only like the characters, but also want to know about the language and culture,” Thuyen said.

Thuyen said the popularity of Chinese wuxia in Vietnam can be traced to the early to mid-20th century, when the country was a French colony.

From 1905 to 1954, a total of 214 Chinese literary works were translated into Vietnamese, and sold quickly, according to Thuyen. Wuxia novels were also frequently republished due to high demand.

Thuyen said such novels were later read by intellectuals, as they saw themselves in the characters and the social conflicts in these books. “Today, most wuxia readers are in their 20s,” she said.

Wuxia-related content is popular in Southeast Asia due to shared culture and customs, such as Confucianism, Thuyen said. People in countries such as Vietnam, whose economy is based on agriculture, are also intrigued by the nomadic lifestyles of martial arts heroes, as this is something they have never experienced.

Scenes from the television series Xuan-Yuan Sword: Scar of Sky. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Scenes from the television series Xuan-Yuan Sword: Scar of Sky. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Noting that the global expansion of Chinese online literature has developed rapidly, Tong from funstory.ai said the market size of the entire industry has risen from 100 million yuan ($14.44 million) to 3 billion yuan in just three years.

At funstory, a Chinese online novel is translated into English through artificial intelligence technology in 48 hours, allowing the platform to update more than 7,000 novels a day and become one of the biggest for online novels entering overseas markets.

Tong Ye said the company will select stories of better quality for international readers, as AI technology can address difficulties in translation, especially with wuxia or xianxia novels, which include many unique terms and phrases related to ancient Chinese culture.

Lee, from YouCloud, said more than 67 percent of Chinese mobile games going overseas were advertised in Southeast Asian markets from January to last month, indicating that the area will remain a major focus for Chinese companies producing games.

As most wuxia games focus on Malaysia and Singapore, or other countries with sizable Chinese communities, Lee said there is still huge potential for such games to gain a bigger foothold in the region with the expansion of online novels and dramas featuring ancient Chinese culture.

Lee said publishers of wuxia games can use human resources and figures from classic dramas when expanding overseas.

“By inviting the older generation of Chinese wuxia actors from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Malaysia to represent these games, they can resonate to a certain extent with the local Chinese,” Lee said, adding that using sentiment and childhood memories is also an effective strategy.

Thuyen said that compared with traditional wuxia novels, the wuxia or xianxia novels of today are not as rich in literary values that reflect social issues. “These novels now mainly serve to meet readers’ or audiences’ need for leisure,” she said.

Scenes from the television series The Legend of Sword and Fairy. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Scenes from the television series The Legend of Sword and Fairy. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Noting that more readers in Southeast Asia are interested in works depicting Chinese society, Thuyen said if wuxia-related content continues to reflect the reality of society and allows readers and viewers to discover issues that they are passionate about, there is a good chance that such works will reach more people in the region.

Tong Weiqiang, from the Singapore Han Cultural Society, said that although wuxia culture is not as popular as it was before, he believes that if new dramas or movies are produced based on Jin Yong’s novels, more people will be attracted to these.

His society is collaborating with libraries in Singapore on reading selected Chinese novels, including Wuxia novels such as Legend of the Swordsmen of the Mountains of Shu, and The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants.

“When it comes to costume drama, most people in Singapore only know palatial dramas and historical dramas, so there is room for wuxia to become more popular,” Tong Weiqiang said.

He added that expanding Chinese wuxia culture mainly depends on whether new works are produced in this genre.

“In the past 20 years, there has been a lack of new, popular wuxia works,” Tong Weiqiang said, adding that new dramas are still based on old works by Jin Yong or Gu Long.

0 Comments